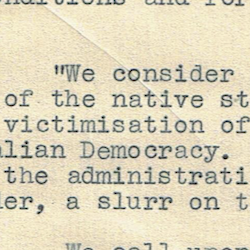

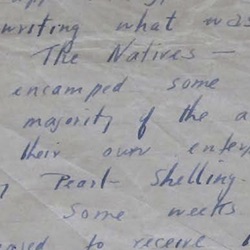

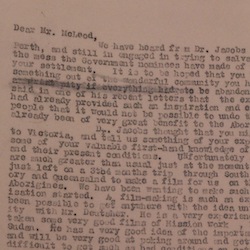

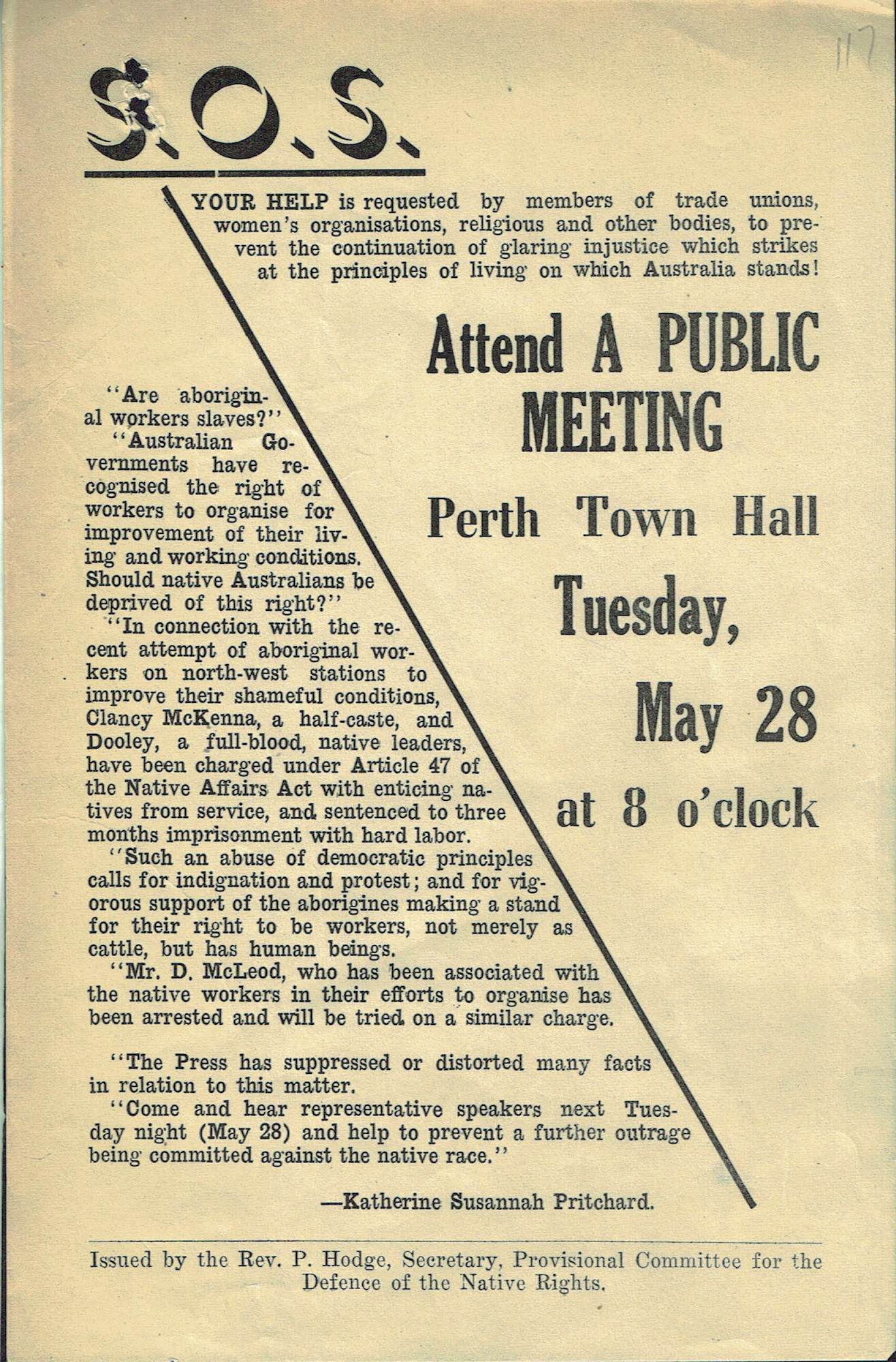

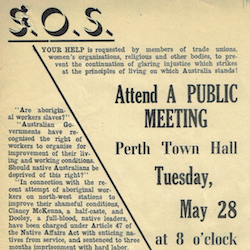

Despite the organisation’s broad base, the involvement of prominent communists, such as author Katharine Susannah Prichard, who wrote this flyer, resulted in it being labelled a communist front organisation by its critics.

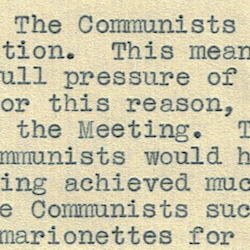

Communist Flyer Urges Public Meeting

Citation

Katharine Susannah Prichard, flyer, issued by Rev. P. Hodge, Secretary, Provisional Committee for Defence of the Native Rights, [May 1946], SROWA, 1945/0800/117.

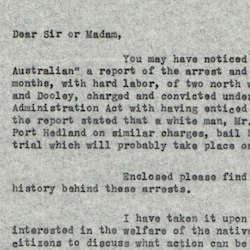

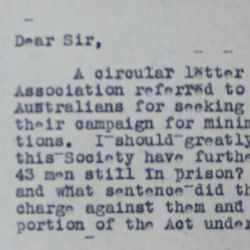

The CDNR assisted the strikers by drawing national and international attention to their cause.

CDNR Brings International Attention to Strikers' Cause

Citation

Committee for Defence of Native Rights to the Secretary-General of United Nations Organisation, New York, 13 June 1946, SROWA, 1945/0800/221-23.

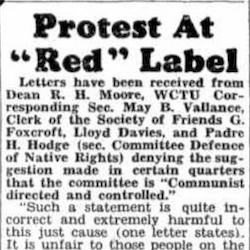

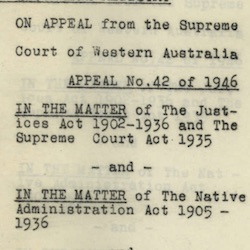

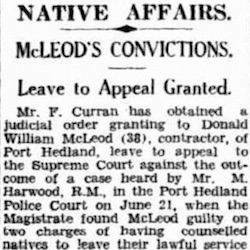

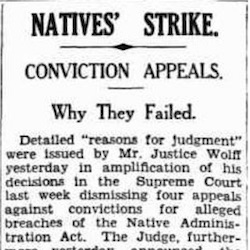

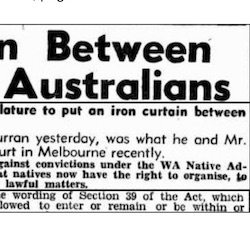

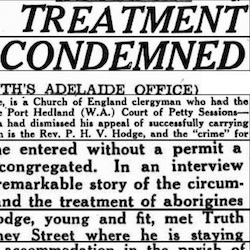

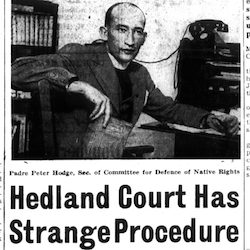

The arrest of CDNR secretary Rev. Peter Hodge, when he visited strikers at the Twelve Mile in August 1946, drew public attention to the oppressive nature of Western Australia’s Aboriginal legislation. His conviction was overturned on appeal to the High Court of Australia, which led to the overturning of a three-month jail sentence imposed on McLeod for the same offence.

Hedland Court Has Strange Procedure

Citation

Workers’ Star, 23 August 1946, p. 6, ‘Hedland Court has Strange Procedure: McLeod Refused Bail.'

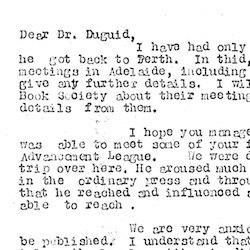

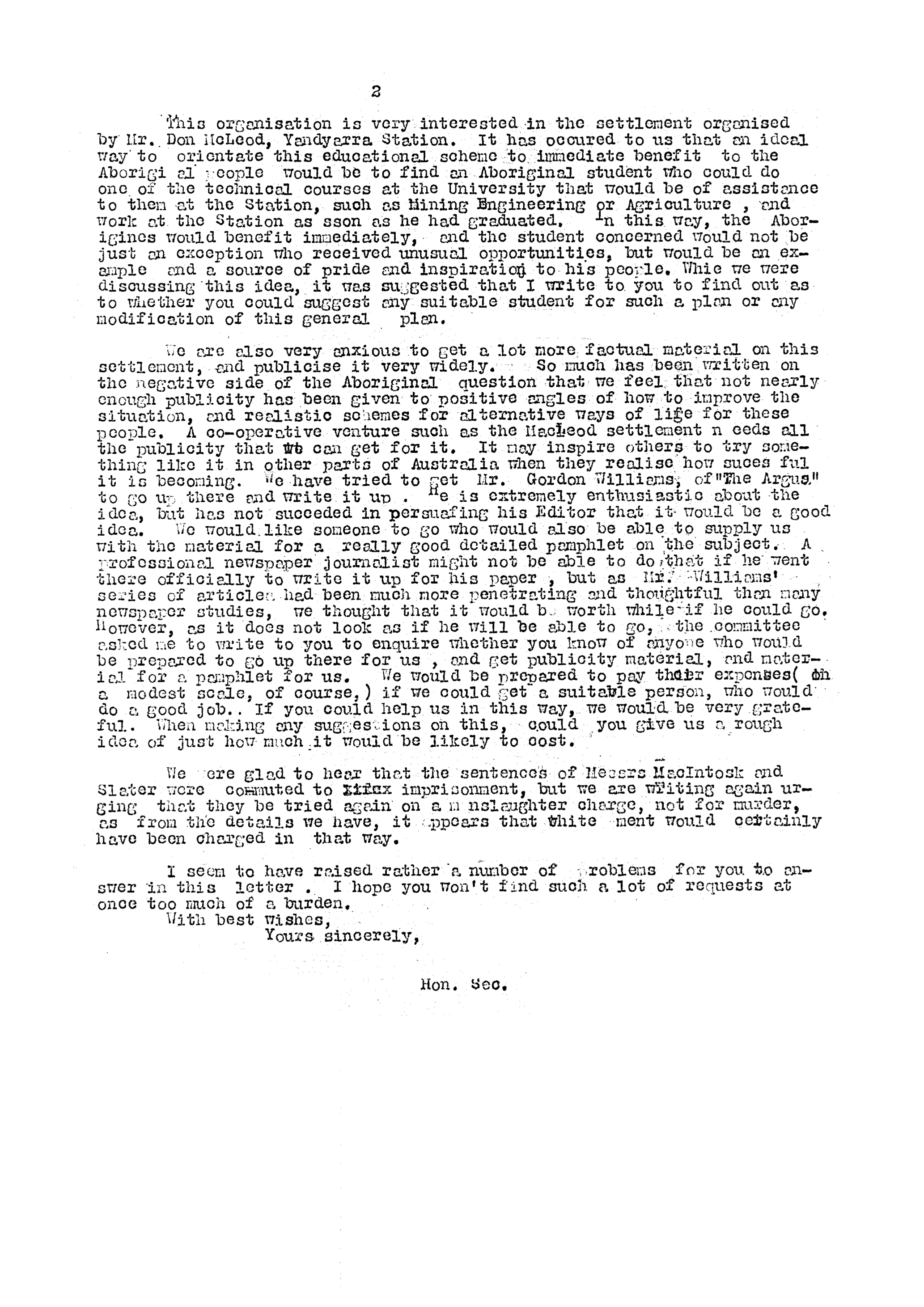

Hoping to see the success of the Pilbara cooperative repeated in other parts of the country, the Council for Aboriginal Rights sought to spread information about the movement as widely as possible. This letter from Andrews to Alfred Nailer Jacobs, an Aboriginal rights activist in Western Australia’s south-west, explains the Council’s interest in and plans for supporting the movement.

Shirley Andrews Explains Council's Support of Strike

Citation

Excerpt of Shirley Andrews to Alfred Jacobs, 21 July 1953, Records of the Narrogin Native Welfare Committee, State Library of Western Australia, MS 3797A/58.

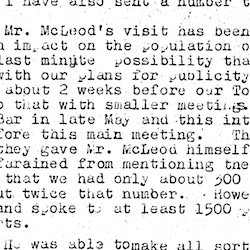

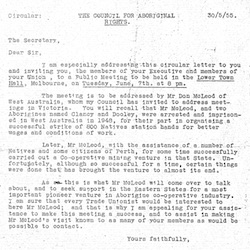

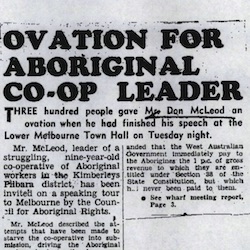

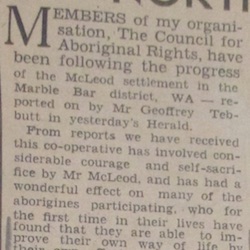

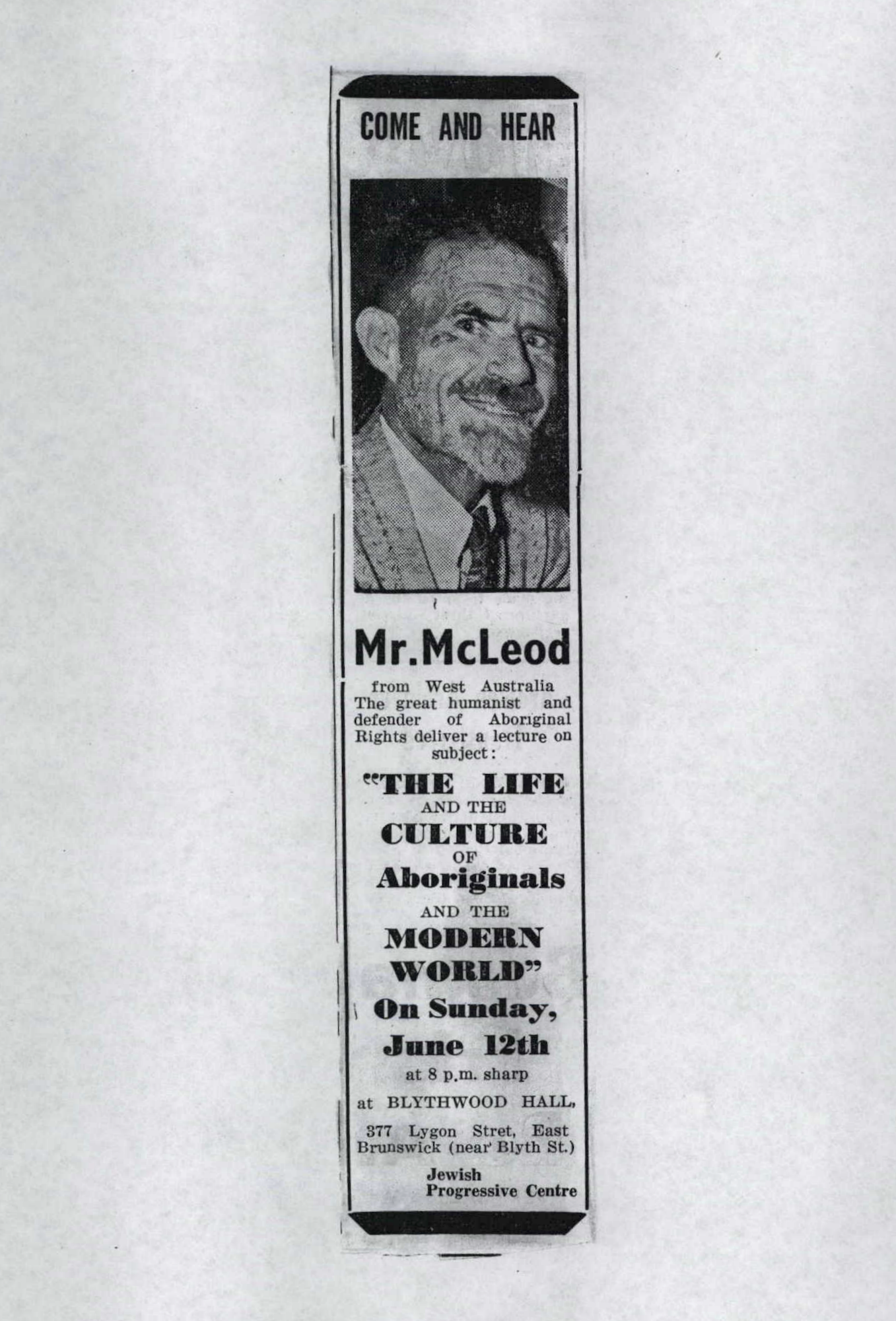

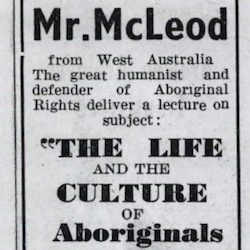

To make the movement better known as an example of what could be achieved by Aboriginal people, the Council invited McLeod to conduct a speaking tour of Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide in 1955, during which he addressed a wide range of audiences.

Come and Hear Mr. McLeod

Citation

Unsourced newspaper cutting, Don McLeod ASIO file 1, National Archives of Australia, A6126 1188.

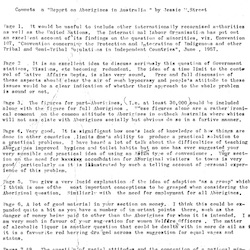

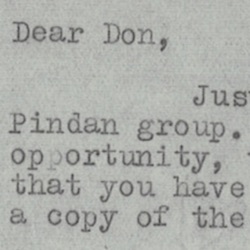

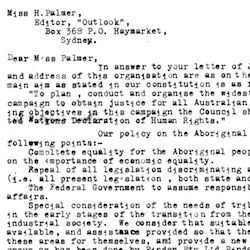

Andrews described Pindan as the most important organisation in the movement for Aboriginal rights in the 1950s.

Shirley Andrews Discusses Pindan's Importance to Aboriginal Rights Movement

Citation

Shirley Andrews to Helen Palmer, Editor, Outlook, 15 July 1957, Council for Aboriginal Rights Papers, State Library of Victoria, MS 12913/2/8/1816.

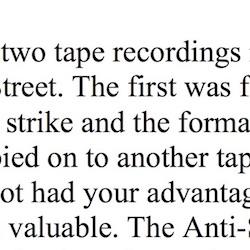

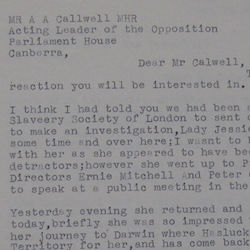

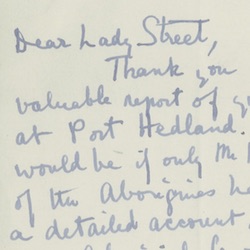

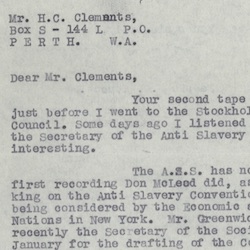

Street received the recordings from John Clement, President of the Western Australian Peace Council, who suggested the information they contained be passed on to the United Nations.

Jessie Street Writes to President of WA Peace Council

Citation

Jessie Street to John Clements, 27 April 1956, Jessie Street Papers, National Library of Australia, MS 2683/10/89.

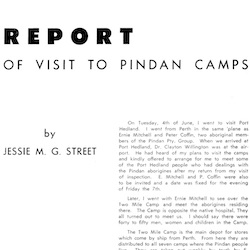

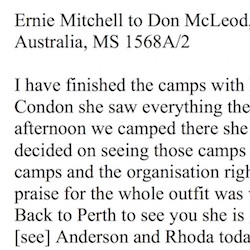

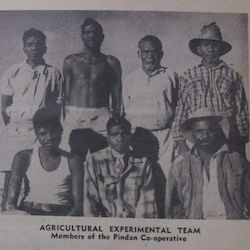

Street was interested in the movement and was highly impressed by the cooperative when she visited Pindan camps in 1957 as part of her tour of inspection of the conditions of Aboriginal people across the country. In addition to her general report, she produced a special report on the cooperative which was reprinted in various formats. The magazine of the Seamen’s Union of Australia, the Seamen’s Journal, reprinted it in two illustrated installments in August and September 1957.

Jessie Street's Report of Visits to Pindan Camps

Citation

Seamen’s Journal, August 1957. pp. 18-19 and September 1957, p. 17, Barry Christophers Papers, National Library of Australia, MS 7992/28.

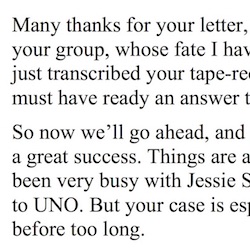

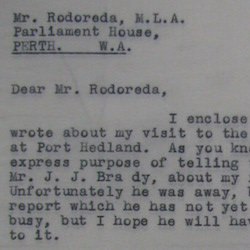

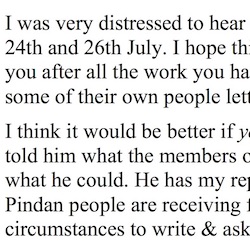

Street continued to involve herself in the group’s affairs, attempting to facilitate more harmonious relationships between Pindan, politicians, government agencies and business partners.

Jessie Street Writes McLeod About Social Service Benefits

United Association

61 Market St.

Sydney

14.9.59

Dear Don McLeod

Thank you for your letter of 2nd Sept.

This is just a line to send you Hasluck’s reply to my letter of August 15 — which you have.

This letter of Hasluck’s, together with his letter of 16th July purports to swear that a wide category of aborigines — in fact all who are not illiterate and nomadic — are eligible for Social Services. Perhaps you can get your aborigines to apply for benefits they may be eligible to receive, and let me [know] the details of their application & the result, also the attitude of the local welfare office. I will take it up with Hasluck. I cannot help thinking he wants to do the right thing & we should strengthen his hand.

No more for the present.

Best wishes

Jessie M.G. Street.

Citation

Jessie Street to Don McLeod, 14 September 1959, Don McLeod Papers, State Library of Western Australia, MS 1568a/9/unnumbered.

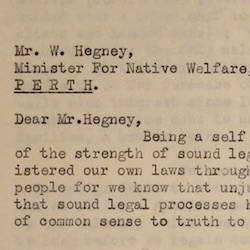

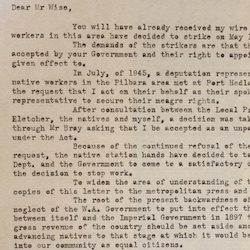

On the eve of the strike in 1946, McLeod referred to the repeal of Section 70 as the root cause of unjust conditions that Aboriginal people were no longer prepared to tolerate, a position that the group continued to maintain in the years that followed.

Repeal of Section 70 Caused Unjust Conditions for Aboriginal People

Citation

Don McLeod to Premier Frank Wise, 30 April 1946, SROWA, 1946/150.

Throughout the 1950s, McLeod argued that the Pilbara movement was a living demonstration of the value and continuing viability of Aboriginal culture and the importance of Aboriginal control of their own destiny, points he believed were undermined by Grayden’s Warburton Ranges campaign.

McLeod Argues for Aboriginal Control of Their Destiny

Citation

Don McLeod to Stan Davey, 21 December 1957, Don McLeod Papers, State Library of Western Australia, MS 1568a/5/230-31.

McLeod and cooperative leaders campaigned vigorously for Aboriginal rights during the 1950s through letters, pamphlets, tape recordings and public meetings. McLeod’s correspondents included politicians, unionists, and activists. Citizenship rights and the right of Aboriginal people to access social service benefits were central to this campaign, as this letter to the senior Labor leader Gough Whitlam shows.

McLeod and Cooperative Leaders Campaign for Aboriginal Rights

Citation

Don McLeod to Gough Whitlam, 9 July 1957, Don McLeod Papers, State Library of Western Australia, MS 1568a/4/55-56.

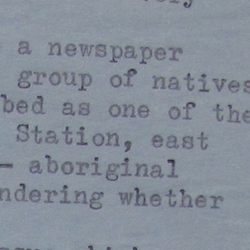

The Pilbara strike and cooperative movement had a profound impact on the lives of Aboriginal people in the Port Hedland and Marble Bar region, but its influence was also felt more widely. In Perth, concern about the imprisonment of strike leaders in 1946 prompted a campaign in support of the strike. This campaign created greater awareness of Aboriginal issues, particularly with regard to the situation in Australia’s north, fuelling the movement for Aboriginal rights in the 1940s and prompting a shift towards a greater focus on the rights of Aboriginal people as workers. During the 1950s, when policies of assimilation were being developed and promoted as the answer to Aboriginal disadvantage, the existence of a uniquely independent and self-supporting Aboriginal community in the Pilbara also caught the attention of activists across Australia and overseas as it demonstrated the viability of an alternative future for Aboriginal people in which community and culture remained intact. Interest in the Pilbara movement as an example of Aboriginal-directed change was further stimulated by the persistent campaigning of Don McLeod and the cooperative leaders, and this gave momentum to Aboriginal rights movement throughout Australia.

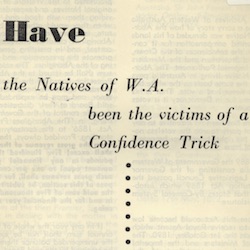

Supporting the Strike - The Committee for Defence of Native Rights

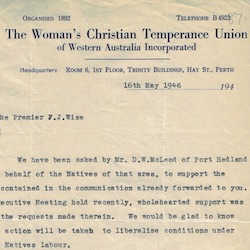

The Committee for Defence of Native Rights (CDNR) was formed in May 1946 by Perth residents who were concerned about the imprisonment of Clancy McKenna and Dooley Binbin. A broad range of people and organisations were involved, including church groups, communists, unions and women’s organisations. Although it was dismissed as a communist front, the CDNR played a significant role in ensuring that government authorities acted within the law in their efforts to put a stop to the strike. At a time when any form of Aboriginal dissent in Western Australia was quickly crushed, usually by removing offenders to distant institutions, the CDNR’s campaign brought national and international attention to the strike, forcing the state government, anxious to avoid censure over its treatment of Aborigines, to deal with the strikers with unaccustomed restraint. Legal representation provided by the CDNR was also significant in challenging the use of Native Affairs legislation to suppress dissent among Aboriginal people. Legal representation enabled Don McLeod to avoid three-months’ imprisonment, while the threat of legal challenge under habeas corpus prevented the removal of strike leaders to institutions far away.

Communist Flyer Urges Public Meeting

Despite the organisation’s broad base, the involvement of prominent communists, such as author Katharine Susannah Prichard, who wrote this flyer, resulted in it being labelled a communist front organisation by its critics.

CDNR Brings International Attention to Strikers' Cause

The CDNR assisted the strikers by drawing national and international attention to their cause.

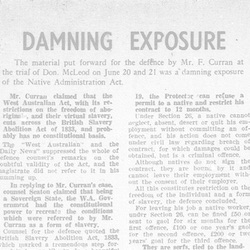

Hedland Court Has Strange Procedure

The arrest of CDNR secretary Rev. Peter Hodge, when he visited strikers at the Twelve Mile in August 1946, drew public attention to the oppressive nature of Western Australia’s Aboriginal legislation. His conviction was overturned on appeal to the High Court of Australia, which led to the overturning of a three-month jail sentence imposed on McLeod for the same offence.

Shirley Andrews and the Council for Aboriginal Rights

At a time when assimilation was being promoted as the solution to Aboriginal disadvantage, a network of activists for Aboriginal rights during the 1950s looked to the Pilbara as a model of Aboriginal-directed change that enabled Aboriginal engagement with the wider economy without dismantling Aboriginal sociality and culture. The Australian organisation most enthusiastic about Pilbara movement was the Council for Aboriginal Rights, whose secretary, Shirley Andrews, was active in seeking and disseminating information about the cooperative that promoted Pindan as a viable alternative to assimilation.

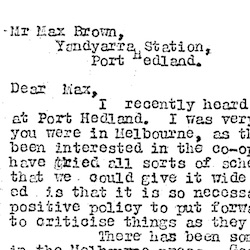

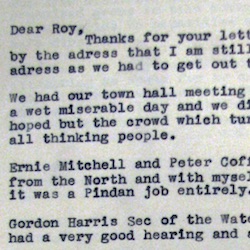

Shirley Andrews Explains Council's Support of Strike

Hoping to see the success of the Pilbara cooperative repeated in other parts of the country, the Council for Aboriginal Rights sought to spread information about the movement as widely as possible. This letter from Andrews to Alfred Nailer Jacobs, an Aboriginal rights activist in Western Australia’s south-west, explains the Council’s interest in and plans for supporting the movement.

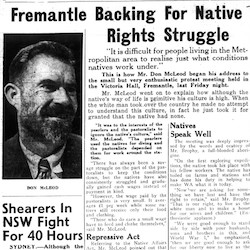

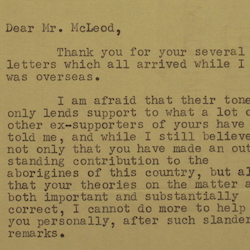

Come and Hear Mr. McLeod

To make the movement better known as an example of what could be achieved by Aboriginal people, the Council invited McLeod to conduct a speaking tour of Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide in 1955, during which he addressed a wide range of audiences.

Shirley Andrews Discusses Pindan's Importance to Aboriginal Rights Movement

Andrews described Pindan as the most important organisation in the movement for Aboriginal rights in the 1950s.

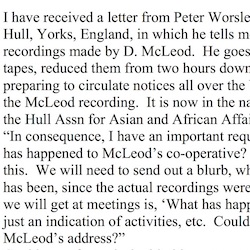

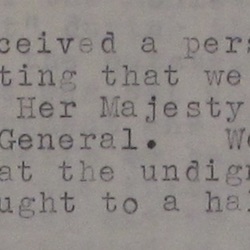

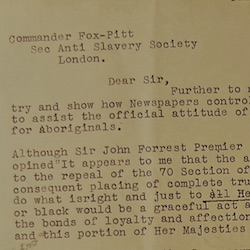

The Anti-Slavery Society and Jessie Street

The Pilbara movement gained more attention in 1956 when London-based Australian feminist and peace campaigner, Lady Jessie Street, a member of the executive of the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines’ Protection Society in London, received two audio tape recordings of McLeod speaking. Interest aroused by these recordings contributed to the Anti-Slavery Society’s determination to bring the question of Australia’s treatment of Aboriginal people before the United Nations. Street’s visit to Australia in 1957, and the survey she conducted in preparation for submission to the United Nations, was a catalyst for the formation of a federal organisation to campaign for rights for Aboriginal people in Australia. Her visit to the Pindan cooperative and her ongoing interest in its affairs brought further attention to the Pilbara movement and increased its influence on the direction of the broader movement for Aboriginal rights in Australia.

Jessie Street Writes to President of WA Peace Council

Street received the recordings from John Clement, President of the Western Australian Peace Council, who suggested the information they contained be passed on to the United Nations.

Jessie Street's Report of Visits to Pindan Camps

Street was interested in the movement and was highly impressed by the cooperative when she visited Pindan camps in 1957 as part of her tour of inspection of the conditions of Aboriginal people across the country. In addition to her general report, she produced a special report on the cooperative which was reprinted in various formats. The magazine of the Seamen’s Union of Australia, the Seamen’s Journal, reprinted it in two illustrated installments in August and September 1957.

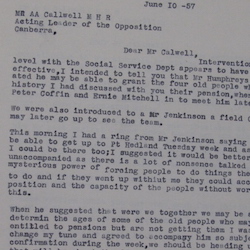

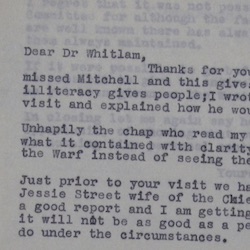

Jessie Street Writes McLeod About Social Service Benefits

Street continued to involve herself in the group’s affairs, attempting to facilitate more harmonious relationships between Pindan, politicians, government agencies and business partners.

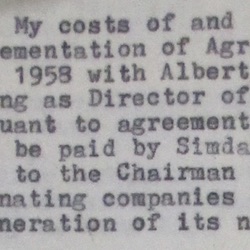

McLeod's Activism and the One Percent Campaign

Throughout the 1950s, McLeod spoke and corresponded with a wide range of people interested in the experiences of this independent community. A central tenet of the Pilbara movement was the claim that Aboriginal people had been betrayed by the 1897 and 1905 repeals of Section 70 of the Western Australian constitution. Inserted as a condition for self-government being granted to the colony by the British Crown in 1890, this section stipulated that one percent of consolidated revenue be expended on the colony’s Aboriginal population. McLeod and marrngu consistently demanded the restoration of this provision, and called for the one percent of state revenue to be paid into a fund directly controlled by the Aboriginal people. This demand was closely linked to a key point: Aboriginal people were capable and must be free to determine their own future and control their own affairs. McLeod therefore objected when claims made by the Western Australian politician Bill Grayden of severe malnutrition among Aboriginal people in the vicinity of the Warburton Ranges, which were documented in a film entitled ‘Their Darkest Hour’, became a focus of the Aboriginal rights movement in 1957. Grayden’s portrayal of helpless people in need of government and mission intervention was, McLeod insisted, ‘diametrically opposed’ to Pindan’s message that Aboriginal people could and must control own affairs, and that mission and government intervention was the problem, not the solution.

Repeal of Section 70 Caused Unjust Conditions for Aboriginal People

On the eve of the strike in 1946, McLeod referred to the repeal of Section 70 as the root cause of unjust conditions that Aboriginal people were no longer prepared to tolerate, a position that the group continued to maintain in the years that followed.

McLeod Argues for Aboriginal Control of Their Destiny

Throughout the 1950s, McLeod argued that the Pilbara movement was a living demonstration of the value and continuing viability of Aboriginal culture and the importance of Aboriginal control of their own destiny, points he believed were undermined by Grayden’s Warburton Ranges campaign.

McLeod and Cooperative Leaders Campaign for Aboriginal Rights

McLeod and cooperative leaders campaigned vigorously for Aboriginal rights during the 1950s through letters, pamphlets, tape recordings and public meetings. McLeod’s correspondents included politicians, unionists, and activists. Citizenship rights and the right of Aboriginal people to access social service benefits were central to this campaign, as this letter to the senior Labor leader Gough Whitlam shows.